The 2030 Agenda SDGs and our survey

On the 1st of January 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development — adopted by world leaders in September 2015 at an historic UN Summit — officially came into force. Over the next fifteen years, with these new Goals that universally apply to all, countries mobilize efforts to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities and tackle climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind.

On the 1st of January 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development — adopted by world leaders in September 2015 at an historic UN Summit — officially came into force. Over the next fifteen years, with these new Goals that universally apply to all, countries mobilize efforts to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities and tackle climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind.

The SDGs, also known as Global Goals, build on the success of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and aim to go further to end all forms of poverty. The new Goals are unique in that they call for action by all countries, poor, rich and middle-income to promote prosperity while protecting the planet. They recognize that ending poverty must go hand-in-hand with strategies that build economic growth and addresses a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and environmental protection.

While the SDGs are not legally binding, governments are expected to take ownership and establish national frameworks for the achievement of the 17 Goals. Countries have the primary responsibility for follow-up and review of the progress made in implementing the Goals, which will require quality, accessible and timely data collection. Regional follow-up and review will be based on national-level analyses and contribute to follow-up and review at the global level.

Find out more about all 17 SDGs > HERE

The Shaping Fair Cities SURVEY

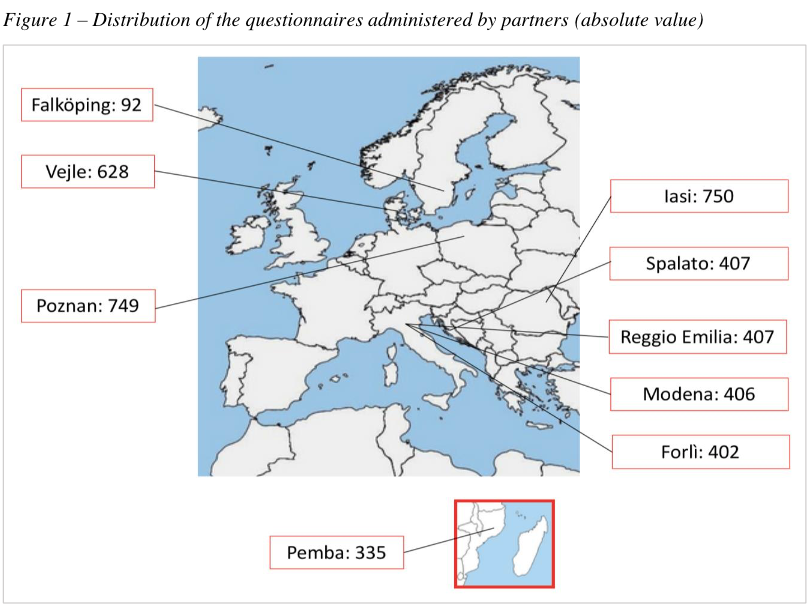

To investigate citizens’ opinion and knowledge about the SDGs, migration, gender equality, climate change, and the role their city should play for sustainable development, a survey was run between July and September 2018 by twelve of the Shaping Fair Cities (SFC) project partners: in the EU (Forlì, Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy; Vejle in Denmark; Patras in Greece; Alicante in Spain; Iasi in Romania; Split in Croatia; and Poznań in Poland) and in two co-applicant partner countries (Scutari in Albania; and Pemba in Mozambique).  From this survey it was inferred that ensuring health and well-being for all (Goal 3), and guaranteeing universal, equal access to drinking water, to adequate hygienic systems and sanitary facilities (Goal 6) were considered as the number one priority in most municipalities, immediately followed by eliminating all forms of poverty (Goal 1), hunger and malnutrition (Goal 2).

From this survey it was inferred that ensuring health and well-being for all (Goal 3), and guaranteeing universal, equal access to drinking water, to adequate hygienic systems and sanitary facilities (Goal 6) were considered as the number one priority in most municipalities, immediately followed by eliminating all forms of poverty (Goal 1), hunger and malnutrition (Goal 2).

Conversely, the protection of the environment and the urgency to find adaptation and mitigation solutions to climate change did not represent a high priority for the interviewees.

Surprisingly, whereas most of the interviewees appeared to agree on the importance of guaranteeing gender equality through the promotion of a culture of equal opportunities and empowerment policies, the fight against gender violence was the worst ranked objective overall. Contrasting views were also outlined in the realm of migration and integration policies as well as regarding the impact that climate change can have on them.

While European citizens registered a very low knowledge on the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, most of interviewees in Mozambique had heard about them. Most interviewees considered important to be informed about SDGs and that the national and local governments should play a part in developing them.

As per the initial confidence with which the interviewees deal with the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, the survey highlighted many gaps, both of theoretical and practical concern.

For instance, sustainable development is still felt as an unclear concept by policy/decision makers, relevant stakeholders and also by the general public. Regarding the connections between migration and gender, the gap is almost total. This means that several societies have not yet endorsed the concepts of gender equality and the difference between gender and sex yet, thus more efforts have to be made for the audience to become acquainted with these terms as well as with those related to migration. Indeed, the awareness of the different forms of international protection in the EU (refugee status and subsidiary protection) and the inherent status they provide, is very low. The difference between these and other instruments to ensure temporary protection (i.e. temporary protection, humanitarian permit) is not gathered. This paves the way to the use (and abuse sometimes) of misleading terms, such as economic migrant, illegal migrant etc.

The main barriers to the integration of migrants, particularly women, in the receiving society registered by the survey concern the language (where the most common languages are not known by the local community and information and services are provided in the national language only); the national origin of the foreigners that may limit their employability; similarly, race and ethnicity can be further obstacles to the integration of foreigners. In this respect, some States, like Poland, affirmed that they are “virtually ethnically homogeneous” and that they should not receive migrants. This argument was dismissed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (C-643/15 and C-647/15, Slovak and Hungary v. Council, 6.9.2017). Likewise, migrants’ religion and culture is deemed to negatively affect their inclusion in the host community.

[A full and detailed international report has been realized by the University of Bologna, merging the local reports, including final recommendation for project campaign purposes]